Japanese Artists

Katsushika Hokusai Artwork, Paintings and Prints

Katsushika Hokusai would become one of the most famous Japanese artists in history, leaving behind hundreds of paintings that continue to amaze and inspire the art public every year.

The Life and Times of Katsushika Hokusai

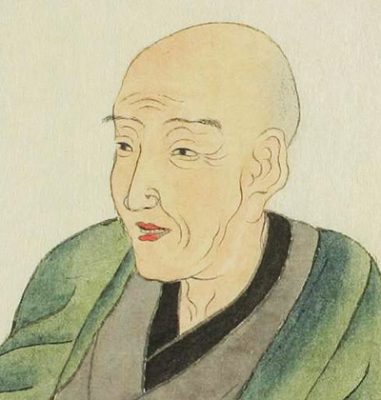

Known as Tokitaro during his childhood days, the man who is now famously known as Katsushika Hokusai showed every sign of a great artist. Like with most of the greatest artists who ever walked the earth, no one noticed his prowess until much later when the grey hair, and especially the balding head, was already setting in. Although his earlier work is considered a marvel by many arts critics, he never gained recognition until he was commissioned to produce a series named thirty-six views of Mount Fuji. One of the works in the series—The Great Wave—won him instant fame.

The Making of a Legend

Born in the tenth year of what was known as the Horekai period (1760) in Edo, Japan, Hokusai was destined to be an artist. His father was an artisan whose trade was mirror-making. It is suggested that since his father’s work involved painting of various designs around the mirrors he made for the shogun, Hokusai learned the art from him. However, he never inherited anything from him, probably because his mother was a concubine. His career began taking shape when he hit 12 and he was sent by his father to a bookshop and lending library, an institution that was frequented by people in the middle and upper classes.

Here, the people entertained themselves by reading books produced from wooden blocks with which the young Hokusai became familiar with. When he was 14, he began working for a wood-carver as an apprentice and left at the age of 18 to work with Katsukawa Shunsho, an artist who used ukiyo-e style. Soon, Hokusai mastered the style which involved wood block prints and paintings. He became the head of the Katsukawa School. Much of the ukiyo-e style was focused on making images of Kabuki actors and courtesans whose popularity in Japanese cities was at its highest. It was common for Japanese artists to take up numerous names. Hokusai had more than thirty pseudonyms, which were more than any other popular artist of his time had taken.

His name changes were frequent and were often associated with the changes in his style and the way he produced his art. Therefore, they are used to break his life into different periods as his career progressed. Hokusai was named Shunro, his first pseudonym, by his master. Under the name, he came up with pictures of Kabuki actors which he made into a series in 1779. While he worked with Shunsho, he married his wife who later died in the 1790s. He married his second wife in 1797 and out of the two marriages, he bore two sons and three daughters. He was influential in making Oi, his youngest daughter, an artist.

Moving Away from Tradition

The death of Shunsho, his master changed things for Hokusai. Instead of breaking him, his expulsion by Shunsho’s chief disciple, Shunko, from the Katsukawa School, helped develop his artistic style. He had acquired Dutch and Cooper engravings which exposed him to European artistic styles. The subjects of Hokusai’s works also changed. Moving away from the actors and courtesans which were the main subjects of the ukiyo-e style, he focused his skills and talents on landscapes as well as different social status of ordinary Japanese people. One of the most popular works produced by the artist at the time is Fireworks at the Ryogoku Bridge created in 1790.

The Big Break

Hokusai took up the pseudonym ‘Tawaraya Sori’ after he became associated with Tarawaya School. Under the name, he came up with surinomo, a number of brush paintings. He also illustrated a book titled kyoka ehon, a collection of humourous poems. He, however, soon gave his name to a pupil and decided to go it alone as Hokusai Tomisa, an artist with no relations to any school. He adopted one of his most popular names Katsushika Hokusai at around 1800. While Katsushika was the name of his birthplace in Edo, Hokusai meant ‘north studio’.

The first works he published under the name were landscapes collections known as Eight Views of Edo and Famous Sights of the Eastern Capital. During this time, he for the first time, got his own students who later added up to more than 50. As the years went by, Hokusai’s fame increased, courtesy of his unique ability to promote himself as well as excellence in his artwork. He was responsible for creation of a portrait of Daruma, a Buddhist priest during a festival held in Tokyo in 1804. It was 600 feet high and made using buckets of ink and a broom. Once, he showed his artistic prowess in the Shogun Iyenari’s court when he was invited for a competition against an artist who was more accomplished in traditional brush strokes.

Hokusai’s work included painting a blue curve on a paper and passing it across a chicken with red-painted feet. He won the Shogun’s heart by explaining that the painting was the maple leaves floating in the Tatsuta River. Hokusai collaborated with Takizawa Bakin, a famous novelist, in producing a series of books. However, they parted ways while they were working on the fourth illustrated book due to differences in their artistic opinions. Nevertheless, the publisher chose Hokusai over Bakin mainly because illustrations were greatly important in production of printed works at that time.

Passion for his own Work

Hokusai insisted that any of his work produced in books should not be changed in any way. Twice, he wrote to publishers and block-cutters who helped produce his designs in a Japanese edition of a collection of Chinese poetry. In one of his letters, he complains that Egawa Tomekichi, the block-cutter had not followed his style in shaping some heads during the production of the book titled Toshisen Ehon.

He also wrote to another block-cutter named Sugita Kinsuke, insisting that he (Sugita) should abandon the Utagawa-school style he had cut the eyes and noses of the figures in and make amendments in order to ensure that they were cut in his (Hokusai’s) style. Evidence of his great influence, the publisher corrected the style even when hundreds of the book’s copies had already been printed.

An Accomplished Teacher

When he was aged 51, Hokusai took up Taito, yet another name. Under it, he produced the Hokusai Manga (random drawings) and art manuals known as etehon. He also came up with Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing which together with the art manuals helped him increase the number of his pupils and earn a living. He published the first book in the Hokusai manga series in 1814. Known by the same title, the modern comics were influenced by the sketches produced in the book.

One of his biggest accomplishments was the Big Daruma. It was a painting done in1817 and measured 18 x 10.8 meters. The people who witnessed the work in its progress at the Hongan-ji Nagoya Betsuin were spell-bound by the skill and talent of the artist. Unfortunately, the original work was destroyed but the promotional handbills survive to date in preservation at the Nagoya City Museum.

National Fame

It was when he changed his name to Iitsu that Hokusai gained recognition as an artist all over Japan. Among his work during that time is Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji which included the Great Wave off Kanagawa, which he is famously known for and helped rescue him from debts. Its increasing popularity inspired him to include ten more prints in the series.

Some of the most popular prints series Hokusai produced during that time includes Oceans of Wisdom, A Tour of the Waterfalls of the Provinces, and Unusual Views of Celebrated Bridges in the Provinces. Additionally, he came up with single images of birds and flowers. They include Flock of Chickens and Poppies, works that are uniquely rich in detail.

Old but Still Mad About Art

Hokusai came up with another popular series, One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, during the period that began in 1834. He had changed his name to Gakyō Rōjin Manji, meaning ‘The Old Man Mad About Art’. Referring to this work, he said that he had not accomplished anything worth noting until he reached the age of 70 even though he had a passion for art since he was aged six and had published numerous drawings since he was fifty.

He said that his understanding of structure of birds, animals, fishes, insects as well as plant life was only in part even at the age of 73. However, he was optimistic that by the age of 86, he would make great progress and further understand their meaning at ninety. At a hundred years of age, he said that he would have reached a level that could only be ‘marvelous and divine. At the age of 110, every of his dot and line would have its own breath.

Fading Away

An unfortunate incident happened to Hokusai in 1839. A fire gutted down his studio and destroyed most of his work. He managed to complete Ducks in a Stream at the age of 87. However, his career was fast fading away as younger artists became more popular. Hokusai never gave up on his passion; he always sought to come up with better work. On his deathbed, he implored Heaven to give him more time to become a real painter.

Other Styles

Some of the other styles used by Hokusai in his works included Shunga, a form of erotic art. A loose translation of Shunga is ‘picture of spring’. It was usually a type of ukiyo-e which used the format of woodblock print. While it entertained people of both gender and all social status, Shunga was surrounded by customs and superstitions. For instance, it was used by samurais as protection against death. Homeowners and merchants also considered it adequate protection against fire.

It was common for brides to be given ukiyo-e showing erotics scenes obtained from the Tale of Genji as presents, and there is evidence suggesting that the sons and daughters of wealthy people used Shunga as a form of sexual guidance. This means that almost everyone in different social classes owned Shunga as personal property.

Artistic Work and Influence

Although he showed the clearest signs of becoming an artist at a tender age and produced many works when he was in his fifties, Hokusai shot to fame only after his 60th year. This was the time he produced some of his most popular works. Top among them is Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, the series that utilized the ukiyo-e style and was completed by 1833. It has 46 prints, with ten of them added after the first publication. One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji was published in 1834. Today, it is considered one of the most significant works in Hokusai’s collection of books featuring landscape pictures.

He is remembered for using his ukiyo-e style to transform art from the traditional portraits featuring famous actors and courtesans—a form which was common in Japan’s cities in the Edo era—to a style that took into account a broader perspective that mainly involved animals, plants and landscapes. Hokusai’s largest work is Hokusai Manga, a collection consisting of 15 volumes holding almost 4,000 caricatures. While 12 of the volumes were published before 1820, 3 were published posthumously.

The sketches are drawings of religious figures, ordinary people, and animals. Most of them take a humourous form and won great popularity during the time they existed. While they are considered to have set the pace for modern manga, one of the main differences between the two forms of art is the fact that Hokusai Manga are sketches of people, animals and objects while modern manga are story-based books using the style of comic books.

Hokusai’s art name and obsession with Mount Fuji was mostly influenced by his religious beliefs. Meaning ‘north studio’, the name Hokusai is an abbreviation of Hokushinsai, which means ‘north star studio’. He belonged to the Buddhist Nichiren sect which believed that the North Star was related to Myōken, a deity. According to Japanese tradition and beliefs, Mount Fuji was associated with eternal life. In the Tales of the Bamboo Cutter, a goddess puts the elixir of life on Mount Fuji’s peak. It was, therefore, believed to hold the secret of immortality, all the more reasons for Hokusai’s strong attachment to it.

Influence out of the Homeland

During his lifetime, Hokusai’s work never moved out of Japan. This was largely because Japan was under sakoku, a policy that put the death penalty on anyone who moved out or into the country. It was only in the 1850s that the American navy under Matthew Perry’s command arrived aboard the ‘black ships’ that Japan abandoned its isolationist policies. Then, diplomats, officers, collectors and artists discovered the existence of woodblock printing used in Japan.

One of the greatest impacts of his work in the West was his tendency to delineate space with line and colour instead of adopting a single perspective. The ukiyo-e styled prints appealed to young artists including Félix Bracquemond, a French artist who first chanced upon a copy of Hokusai Manga, the sketch book, at his printer’s workshop.

However, most of the first Japanese prints that found their way out of the country were just contemporary works of art, and not the masterpieces produced earlier by older artists like Hokusai. In fact, many of them were used to wrap commercial goods. On April 1 1867, the Champ de Mars saw the opening of Exposition Universelle. For the first time ever, there was a Japanese pavilion showcasing ukiyo-e prints. French artists got a chance to meet Japanese print and understand how it was produced. Soon Claude Monet acquired 250 prints from Japan. Among them were 23 by Hokusai. Influenced by Hokusai’s depiction of one subject over many images, Monet produced series of poplars and grainstacks, Waterloo Bridge and Rouen Cathedral.

Hokusai’s influence on Monet’s art was not enough. It went on to his way of living. His Giverny garden takes the design of a Japanese print, including the use of bamboo and arcing of the bridge. Additionally, his wife took to wearing a kimono. While Monet was influenced by Hokusai’s landscapes, other artists fell for the human and animal forms. One of them is Edgar Degas who found inspiration for his fin-de-siècle women depictions in France from Hokusai’s manga.

While the dancers have their faces in profile and backs curved like in Japanese portraiture, Hokusai’s influence is in the bathers. Additionally, Degas’ etching of Mary Cassatt at the Louvre has all the likeness to Hokusai’s manga. While Casatt puts her weight on one leg, she imitates the pose of a woman who is being pulled away by a wild horse. Another great benefit derived from the entrance of Japanese print, especially Hokusai’s, into the French art scene is the raising of the reputation of the graphics arts industry. Printmaking was seen as a respectable enough medium for artists. A lover of Japanese prints, Cassatt owes a good deal of her modern printmaking to the introduction of Japanese art to France.

One other artist who owe his success to arrival of Japanese art in France is Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. While he began as a painter, he almost completely took up printing and poster-making soon. It is evident that ukiyo-e style is at work in the making of his Divan Japonais poster. Jane Avril, the cancan dancer is portrayed in a severe, Oriental profile. Moreover, Hokusai’s influence is clear in the big solid colour panels that frequently appear in posters and prints done by Lautrec. Hokusai and Japanese art in general are responsible for influencing the birth of a new style known as Jugendstil in Germany or Art Nouveau.

It is widely accepted that without Hokusai, there would be no such thing as Impressionism which was exhibited by such artists as Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet. Some of the artists who collected his woodcuts include August Macke, Franz Marc, van Gogh, Klimt, Gauguin as well as Monet and Degas. Peitschenhieb by Hermann Obrist shows all the signs of Hokusai influence and became an example of the Impressionist movement.

Summary

Edo’s claim to fame may be giving way to what is now Tokyo, Japan. The world, however, owes it one more for producing one of the most talented and persistent artists of his time. Trained as woodblock cutter and accomplishing great success as a commercial artist, Hokusai is remembered for his unique range of both subject and style. Even when he gained national recognition for work produced in later years, he in the true spirit of an artist—he always insisted that the best was yet to come.

He believed that his talents and skills would become sharper as he aged. While he produced different works with diverse levels of quality throughout his long career as an artist, the best of them were completed when he was in the early 70s. The destruction of his studio and many of his artworks by fire did not deter him from producing more and he worked till he breathed his last breath aged 90.